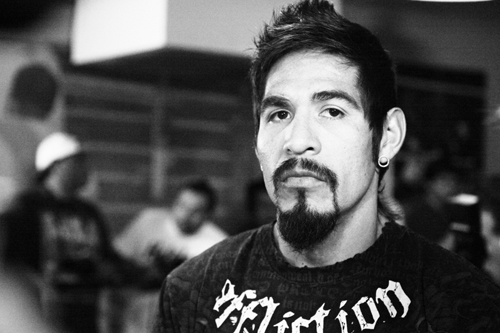

Antonio Margarito was finishing his third set of abdominal crunches on a breezy evening in late April when he was told of the confrontation unfolding on the street outside the Gimnasio Azteca. The newly crowned IBF welterweight champion bounded up the steps of the ratty basement-level Tijuana gym and stopped at the entrance to survey the scene.

A half-dozen federal policemen had spilled out of four white Silverado pickup trucks and surrounded a young man who had been rummaging through the trunk of a plate-less SUV parked directly across the street. Eight more officers stood by, gripping AK-47 assault rifles. Some wore black ski masks. All were decked out in full battle gear.

Margarito strode over to the cops and identified himself, smiling and shaking their hands. The SUV was not stolen, he assured them. It was a present he had just given to the man at whom the police were pointing their weapons: his pad man and lifelong barrio buddy, Jesús Armando Pérez Cortez.

Margarito assured the cops that the vehicle would be registered without delay. Backs were slapped and the champ was congratulated on his most recent victory, a sixth-round knockout of Kermit Cintrón on April 12 in Atlantic City. Jesús was free to go. Celebrity, it seems, has its perks even in a violent, drug-ravaged town like Tijuana.

The tension in the border city is palpable. Bodies are found on the streets almost every morning, and kidnappings have become commonplace. Thirty-six hours after the license-plate mishap involving Pérez, 15 people were killed and six injured in a bloody shootout between rival drug-trafficking gangs and police.

But as the cartels battle each other and the authorities for supremacy on the streets, Margarito sticks to his training routine, tuning out the mayhem and shrugging off inconveniences such as the ubiquitous police roadblocks. “The drugs and violence are everywhere,” he says, “but I stay focused and walk my own path.”

When not in the gym, the champion drives around in a sleek late-model Mercedes SUV and drops in at elegant restaurants where he signs autographs jovially and eats indiscriminately. He’ll burn off all the calories, he explains, in his arduous daily workouts.

The so-called “Tijuana Tornado” is, in fact, a fitness freak. He resumes full workouts barely a week after each fight, rising to run in a popular municipal sports complex at 6 each morning, logging two hours of light weight training under the supervision of a bodybuilder (another close friend from the barrio) at a nondescript downtown gym a few blocks from Tijuana’s infamous red-light district. Finally, he trains diligently with Pérez at Gimnasio Azteca.

While Margarito may be a destructive whirlwind in the ring, punishing his opponents with powerful hooks and crumpling uppercuts (he knocked out Cintrón with a vicious blow to the liver), outside the ropes he’s a prankster who teases his friends relentlessly and laughs gleefully when recalling the time five years ago that, at the mature age of 25, he caused a minor panic outside a mall by setting off a cherry bomb. To anyone who knew Margarito as a boy, this is anything but a surprise.

The fighter grew up in a cramped hillside house in Tijuana’s hardscrabble Zona Francisco Villa, sharing two rooms with his father, mother, older brother and three younger sisters. He and his barrio friends were not criminals, but they caused more than their share of trouble. They rolled tires off hilltops, sending them crashing down on neighbors’ roofs, broke windows, and tampered with fuse boxes, temporarily enshrouding nearby homes in utter darkness.

“I never ran with a gang,” says Margarito, “and drugs and alcohol didn’t appeal to me, but I definitely liked to stir things up.”

That Margarito wasn’t drawn into the vortex of violence and drug abuse that swallows so many Tijuana youths is miraculous. “I would step outside to run at dawn and see some of my friends doing drugs,” he says. Now, driving around town listening to his favorite rancheras, he somberly ticks off a list of less fortunate friends from Zona Francisco Villa.

“One was gunned down in jail,” he says, “and another in front of a pharmacy. A third caught a bullet in his house. Two others went crazy from crystal meth.”

Margarito credits his parents and boxing for his survival. “They were a good example,” he says of his father, Antonio Sr., and mother, Consuelo. “And I wanted to improve my life, so I spent a lot of time in the gym.”

Antonio Sr. sold lamps and moonlighted as a night watchman, but he took the time to inculcate his sons with discipline. He introduced the older boy, Manuel, and Antonio to the boxing gym when Antonio was 8 years old, and fanned their interest in the sport by taking them to see pro fights.

But, at first, Antonio was not a pliant pupil. “I sent him out early to run,” Antonio Sr. recalls, “but someone told me he was deceiving me. He’d wet his head out there and come back pretending he was sweating.” So, Antonio Sr. snapped a towel at his son until he worked up a legitimate sweat dodging its tail.

The boy turned pro in 1994, at age 15, but his career was slow to take off because his trainer-manager, Joe Valdez, pitted him against much older, more experienced fighters.

At 18, Antonio had a mediocre 9-3 record, but he still showed promise as a tenacious brawler with a granite chin. After putting himself in the hands of the more cautious Los Angeles-based managers Francisco Espinoza and Sergio Díaz, he quickly climbed the ranks, winning 16 straight fights over the next four-and-a-half years and signing with influential promoter Top Rank along the way.

Manuel Margarito was less fortunate. He struggled after turning pro in 1993, and was forced to split his time between work (to support his wife and daughter) and the gym.

In October 1999, Antonio and Espinoza were in the lobby of a Holiday Inn in Fort Worth, Texas, on the eve of his bout with journeyman Buck Smith, when Espinoza was called to the reception desk.

“When he picked up the phone I got a bad feeling,” says Antonio. “Then he looked at me and turned away. That’s when I knew.” Manuel had been gunned down in his home. The reason why is still unknown. But the cruelty of his death would be compounded a week later when Manuel’s young wife gave birth to their second child.

That night Antonio walked the streets of Fort Worth in a daze. But when he returned to the hotel at 3 a.m., he told Espinoza that he would fight the following evening anyway. He took a sleeping pill and rested enough to put Smith away with a body punch in the fifth round. “I don’t know how I won,” he says, “but I know Manuel was with me.”

Margarito continued to fight through the pain, and he developed into one of the hottest prospects in his division. He won the WBO welterweight title in 2002 with a decisive beating of Antonio Díaz and defended it seven times over the next four years. By 2006, he had joined the coterie of elite fighters pressing for a date with pound-for-pound king Floyd Mayweather Jr. But Mayweather spurned Top Rank promoter Bob Arum’s offer of $8 million (a career-best purse at the time) to fight Margarito.

“Mayweather ducks everyone who has a chance to beat him,” says Arum, “and Margarito was a serious risk — a crowd pleaser with an iron chin.”

The following summer, Margarito’s stock fell considerably when he lost his WBO title to rangy southpaw Paul Williams by unanimous decision. But his decisive knockouts of Golden Johnson in November 2007 and Cintrón last April have set the stage for the mega-fight (and mega-bucks payday) for which he has been clamoring for years, against WBA welterweight champion Miguel Cotto on Saturday in Las Vegas.

The Cotto-Margarito matchup should be a barnburner. Cotto has never lost a professional fight, and Margarito has been floored only twice in his career — and both times he ended up wining the fights.

Given the boxers’ aggressive styles, one can expect a frenetic pace and riveting toe-to-toe combat. Margarito’s best defense (his only defense, really) is his relentless aggression. He’s a dangerous fighter who attacks continuously from myriad angles. Cotto, on the other hand, can box or brawl with equal effectiveness, as he demonstrated in his technically sound win over Shane Mosley in November.

With Margarito’s pronounced height and reach advantages (he’s 5-foot-11, with a 73-inch reach; Cotto’s 5-foot-7, with a 67-inch reach), Cotto would be best served by keeping his distance and trying to outpoint Margarito. But don’t count on it. Tempers should flare up in the later rounds, and the two best welterweights in the business (with Mayweather’s retirement) will likely trade blistering blows until one or the other drops.

Should Margarito beat Cotto, he will have earned the right to a mammoth payday against Oscar De La Hoya (though he might retire before then). If a fight with the Golden Boy does materialize, Margarito plans to use the proceeds to branch out into real estate. But he’s well aware that his time in Tijuana may have run its course. He lives in an expansive five-bedroom home with his childhood sweetheart, Michelle, and two of her younger brothers, five minutes from the comforting familiarity — and troubling violence — of his old neighborhood.

Tijuana is a tough place to raise a family these days, even for Zona Francisco Villa’s favorite son.♦