It was November 1997, and Fernando Valenzuela was a 37-year-old pitcher suffering from arm fatigue and losing his battle to stay in shape. Three months earlier he’d been let go by the St. Louis Cardinals, and it appeared then that after 17 years in the majors, he was done as a player. Yet here he was, standing on the mound in the uniform of Los Naranjeros de Hermosillo of the Mexican Pacific League, the same winter league in which, as a 16-year-old, he’d struck out his first batter as a pro. ¬∂ “I thought I might be good for one more year,” Valenzuela says now. “I needed to keep playing. I am Mexican. I wanted to put on a good show in front of my people.” In truth, he just couldn’t give up the game.

So Valenzuela, the once-beloved object of Fernandomania and the most prominent member of Mexico’s pantheon of peloteros, pitched for four months over each of the next five winters, winning 13 of 21 decisions, until his contract with Hermosillo expired in January 2002. He was 41, and there was no place left to play.

By then his oldest child, Fernando Jr., was a standout first baseman at Glendale (Calif.) Community College, living at home in Hollywood Hills with the family. The following fall, Fernandito, as the son is affectionately known, would leave for UNLV, to enroll for his junior year and play Division I baseball.

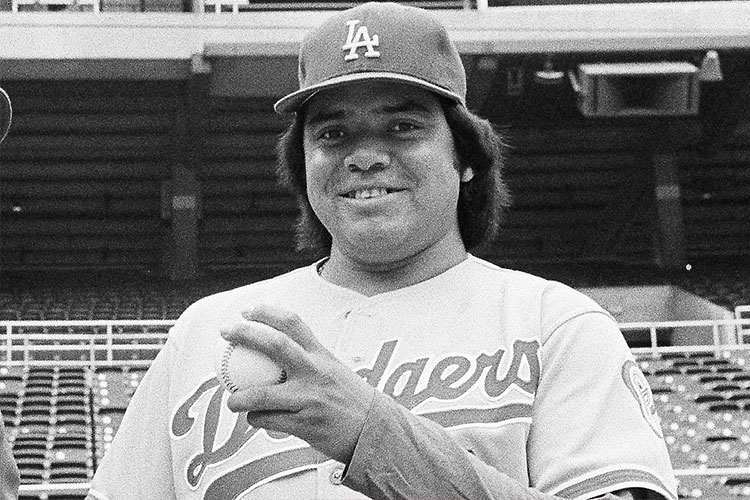

A carbon copy of his father, with the same jet-black hair, round cheeks and baby-faced smile, Fernandito also shares his father’s passion for the game. “A lot of kids get to the point where they say, ‘I don’t want to play baseball anymore,'” Fernandito says. “I’m different. I want to get as far as I can and do the best that I can. That’s something that has been passed on to me through my dad.”

Valenzuela drove his son across the desert and helped him settle into a rented off-campus condo. In the first week of fall practice, Fernandito turned heads with his bat and his glove, and this spring he led the Rebels to a 47-17 record and an appearance at the NCAA regional final.Many times during the season his father was there to watch. And as he stood in the stands and soaked in his son’s success, the older and more famous Valenzuela finally began to accept his own exit from the game.

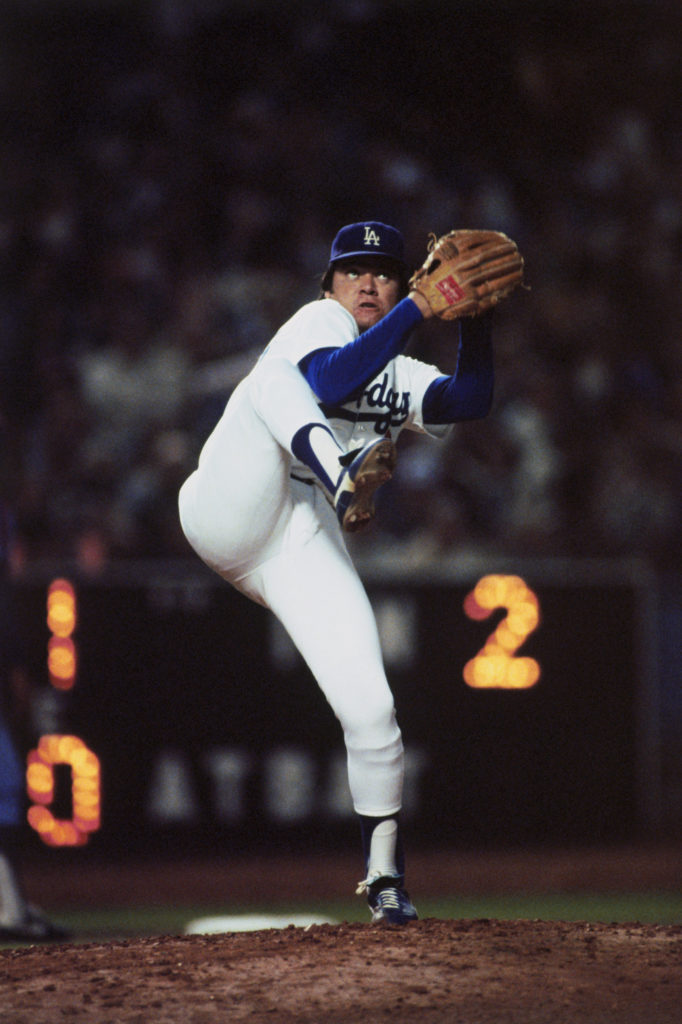

It’s not easy coping with the ultimate truth that every player’s final deal is a one-way trade out the stadium door, a sometimes brutal segue into una vida sin beisbol. For Fernando (El Toro) Valenzuela, who as a 20-year-old rookie lefthander in 1981 electrified Southern California with his aura of youthful invincibility on the mound, it has been a particularly rough retreat. So much early success, so much fawning attention. Just imagine being in his spikes in the spring and summer of ’81….

After lefthander Jerry Reuss pulled a leg muscle 24 hours before his scheduled Opening Day start, Valenzuela got the call to start the season, and he shut out the Houston Astros 2-0 on five hits. By mid-May he was 8-0 with a 0.50 ERA, and Fernandomania was sweeping the country. Relying on a screwball (lanzamiento de tornillo) that he had learned a year earlier, he threw seven complete games and five shutouts–including 36 consecutive scoreless innings–in those first eight starts.

He was the National League’s starting pitcher in the All-Star Game (he tossed one scoreless inning) and finished the strike-interrupted season with a 13-7 record, a 2.48 ERA and National League highs in strikeouts (180), complete games (11) and shutouts (eight). He even hit .250 and had two game-winning RBIs. With a loopy windup and eyes that rolled skyward in the

middle of his delivery, Valenzuela was the first player in either league to win Rookie of the Year and the Cy Young Award in the same year.

The tidal wave of attention that season would have been enough to drown any 20-year-old, to say nothing of a foreigner hampered by the language barrier and overwhelmed by El Norte’s fast-paced lifestyle. More than 20 years later Latino athletes still struggle to adjust to life in the U.S.; for Valenzuela everything was magnified a hundredfold. “Pitching in front of the huge crowds was the easiest part,” he says. “The difficulties were away from the game.” It was in the relentless glare of the media that he felt most vulnerable.

Valenzuela can recall his frustration in trying to answer reporters’ questions–which he willingly attempted to do in press conferences at the start of every series on the road–even after he got a translator he was comfortable with, Dodgers

Spanish-language announcer Jaime Jarrin. New York was the most intense, of course. “I remember entering a room and being stunned,” says Valenzuela. “There were about 60 photographers, and that’s without counting TV cameras and journalists.”

He put the finishing touch on his rookie season by going 3-1 witha 2.22 ERA in three postseason series, and the Dodgers won the World Series in six games over the New York Yankees.

Act II? Are you kidding?

Valenzuela spent 10 mostly successful seasons in L.A., his best one (after his rookie year) coming in 1986, when he was 21-11 with a 3.14 ERA, 242 strikeouts and a league-high 20 complete games. And he was not just a popular player and a crafty lefty- he was a marketing juggernaut. He galvanized the interest of millions of Latinos and was the main reason the Dodgers had the largest home attendance in team history in ’82 and ’83. “It happened so fast it was like a forest fire,” says Tommy Lasorda, his manager at the time. “He had tremendous impact on the Dodgers, the fans and all of baseball. Everywhere we went everyone wanted to see this lefthander from Mexico pitch. He attracted crowds on the road and at home like you’ve never seen. Fernandomania was something I will never forget.”

Valenzuela’s cashable celebrity opened corporate America’s eyes to the idea of marketing Hispanic players to a Latino audience hungry for heroes in their own likeness. The young phenom swung open the doors that future Latino megastars like Alex Rodriguez and Sammy Sosa would walk through.

In the six seasons from 1982 through ’87, Valenzuela averaged 266 innings pitched per year and 7 2/3 innings per start, heavy work for any pitcher and especially for a young arm that threw so many screwballs. He missed eight weeks of the ’88 season with a shoulder injury but two years later pitched a no-hitter against the St. Louis Cardinals. Arm weary, he went 13-13 with a 4.59 ERA in 1990, and the Dodgers released him in spring training the following year. Over the next six seasons Valenzuela spent time with five major league teams, did a stint in the minors and went home to play in the Mexican summer league twice. He recaptured a bit of the magic in ’96 when he went 13-8 with a 3.62 ERA to help

the San Diego Padres win the NL West.

By the time the Cardinals released him, in 1997, Valenzuela at least recognized that his big league career was over. “I knew I couldn’t take the intense training and preparation required to compete at the major league level,” he says. “But I didn’t want to announce my retirement. I wanted to keep pitching at whatever level I could.”

For Fernando and Fernandito, the generation gap is little more than a fissure. To be sure, padre and hijo have their differences. (For one, Dad is partial to las Nortenas, traditional Northern Mexican folk songs; his son opts for hip-hop and rap.) But the family bond is strong, and is for all the Valenzuelas, including Fernandito’s younger siblings Ricardo, 19, a 6’4″ offensive lineman at Glendale Community College; Linda, 17, a high school volleyballer at Immaculate Heart; and Maria Fernanda, 12, who favors softball. When Fernando and Linda, his wife of 21 years, bought a place for Fernandito to live in Henderson, Nev., 15 minutes from school, they chose a three-bedroom town house with plenty of room for visiting family members in town to watch UNLV home games.

What those visitors saw was a soft-handed 5’11”, 220-pound first baseman who batted .337, with 14 home runs and 75 RBIs, and was named Mountain West Conference Player of the Year. “He knows what pitches he can handle and likes to get deep into the count,” says Rebels coach Jim Schlossnagle. “And he’s the best defensive first baseman I’ve ever coached. His glove really saved us this season.” In the major league draft on June 3 Fernandito was selected in the 10th round by the Padres; last Thursday, in his professional debut with the Single-A Eugene (Ore.) Emeralds, he went 4 for 6 with two homers, a double and six RBIs.

What’s more, he’s achieved all this without feeling any of the pressure of following in his father’s famous footsteps. “Fernando loves to talk about his dad,” says Schlossnagle. “He’s always talking about what an honor it is to have the same name.” Says Dad, “I’ve always tried to give my son space. I don’t want him to play this sport because I did. I want him to feel it. To carry it in his blood.”

Fernandito is 20 now, the age at which his father made his spectacular debut with the Dodgers. But whereas Fernando grew up the youngest of 12 children crammed into a five-room adobe farm house in Etchohuaquila, Mexico, Fernandito was nurtured in an eight-bedroom L.A. manse. (“I’ve had it much easier,” he says. “I got a chance to go to college. My dad didn’t have that opportunity.”) Valenzuela credits his wife’s business savvy for enabling the family to live well since the end of his major league career. In the mid-1980s Linda persuaded her husband to invest in real estate, and she laid the groundwork for a realty business that has grown to include residential complexes in three states.

The Valenzuelas also still own the small ranch-style Hollywood house they bought 15 years ago to serve as an office. It houses a Fernandomania museum of sorts, displaying his Cy Young trophy, plus magazine covers and a photo gallery of memorable moments on and off the field (including shots of Valenzuela meeting with presidents Reagan, Bush Sr. and Clinton). It’s a comfortable setting for Valenzuela to meet with business associates and visiting media, and it’s also where he sifts through boxes of fan mail and signs each ball and magazine cover that arrives with suitable return packaging.

The Dodgers recently announced that Valenzuela will be making a comeback with the team, not as a pitcher but as a pitchman, representing the club at civic functions and charity events as well as working as an analyst on the Spanish-language radio network that broadcasts L.A. games. “We’ve been trying to find the perfect situation for Fernando,” said Derrick Hall, the Dodgers’ senior V.P. of communications. “This fits his personality well, and he will bring magic to what is already the best Spanish broadcast team in baseball.”

El Toro still has his passion for the game, but he’s happy enough now just to watch it and contribute in smaller ways. Fernando has given way to Fernandito, and there is comfort in knowing that the Valenzuela legacy is in soft hands. ♦